I arrived in Tilting on a sunny and surprisingly hot August day. Tilting harbour was calm, yet I could hear crashing waves.

Walking.

Listening.

The waves louder with every step.

After 15 minutes was a place of comfort. A means to reconnect to something I missed for years but hadn’t realized until I discovered Oliver’s Cove. I don’t know what I missed. Three weeks I searched to determine this intense feeling and the draw to return daily.

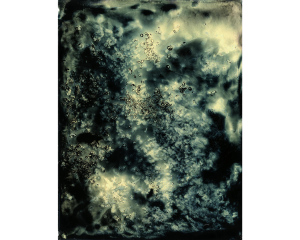

I focused on the traditional picket and longer fences that defined the centuries old garden plots surrounding the water. The vegetables taste different, unmistakably infused with salt water. Curiously off, but in a good way. Glass is a fragile substrate, and I did not fight the weak bonding of the collodion to the surface – a conscious decision that seemed to make sense for the fences, opposed by the tintypes of the rocks and ocean. A certain permanence and strength exist in these natural elements reflected in the surface of blackened aluminum. I used salt water to stop the development of each plate made onsite using my portable wet plate collodion darkroom. Sediment from the ocean and salt from the water mixes and interacts with the images of the fences and the cove – suspended in the collodion.

The photographs depict—but are also shaped directly by—their environment.

Perhaps a collaboration with the environment, underlying what we do not see, and what continue to search for; the energy within the land and the ephemeral intersection of light and time on sensitized glass or metal.

(dis)regard explores the notion of transition in the built environment and sense of place through the lens of three communities in Fife, Scotland transformed by socioeconomic change, loss of industry and, in some cases, population changes such as out-migration. I am continuously drawn to the effects of change on the built environment and the evidence of past histories. This work was created in Leven, Methil and Buckhaven. My intention was to investigate everyday areas and in-between spaces that have fallen into disuse, or have been re-invented and reveal efforts of regeneration.

As an outsider to this area, I am also interested in the notion of place: “Places have influenced my life as much as, perhaps more than, people. I fall for (or into) places faster and less conditionally than I do for people.” Lucy Lippard, Lure of the Local (1997). Whether as a local or an outsider, I have always experienced a strong emotional response to place. Strangely, it’s often the memories triggered by new places that make me feel connected to unfamiliar surroundings—which I seek to represent and communicate through my work.

Living in Atlantic Canada offers the experience of four, extreme seasons. While many people prefer the warmer seasons, I am comforted by the cold. Each spring I find myself wanting to extend the winter, searching for and excited by every little patch of snow that is somehow surviving in the shadows of the landscape. snow is an attempt to preserve the impermanence of the changing climate. Each of these cameraless images is a direct record of working on-site, selecting handfuls of snow, and placing them on a light sensitive piece of metal, preserving them through silver and light. Working this way facilitates a deeper connection to the landscape. I slow down and become more aware of the components that make up our environment.

When Canada’s one-room schools gave way to centralized schools, there was a shift in our communities: in how we were taught, in where and how we came together as a community, and in the physical landscape of our hometowns and cities. These schools, built at the turn of the Twentieth Century, have a unique presence within the architectural composition of the Atlantic Region. Each school is singular in its details, yet a commonality exists among them. These structures speak to our notions of “community” and reflect the present as much as they reveal the past. While some communities have raised money to renovate and revere the local heritage they see in their schools, others have engaged in urban camouflage: turning the schools into condominiums, offices and public spaces, or simply leaving them neglected and forgotten.

As a child, I grew up in Topsail, Newfoundland, within a ten-minute walk of the Atlantic Ocean. Many days were spent exploring the barren coastline and the roads and trails in my community. Trace explores my ongoing relationship with this landscape over the 25 years since I left it. My childhood memories act as a framework to approach the idea of sense of place and my relationship with the landscape of Newfoundland.

The photographs themselves are also shaped by this environment: All processing is done on-site using a portable darkroom. The images are made using the wet-plate collodion process to produce glass negatives. The introduction of the elements of the environment such as local water (rather than distilled), changes in temperature and humidity, or rain falling on a coated plate, all affect the chemical reactions that are integral to the process—resulting in physical imprints on an image such as cracking, crystallization, and voids. These unpredictable elements that interrupt the landscape’s image are just as important as the place itself: like memory and emotion, they shape how a place is seen or known.

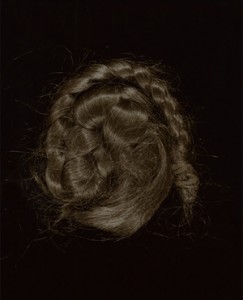

My interest in memory, change and absence—of noticing what is gone and what has been left behind—is explored in memento. This series focuses on the historical practice of saving hair—a tradition in many cultures—to connect to the soul or to remember an ancestor. In memento, I have photographed these extensions of the body that have been saved as a kind of souvenir, or memory. The hair physically exists and represents the absence of a person, whether dead or alive. The decision to print the 4×5” film as P.O.P (Printing Out Paper) contact prints, a process developed in the late Nineteenth Century, is intended to complement the timelessness of the practice of saving hair.